Video Script

TRT: 00:03:04

Start: 00:00:00

Reporter: They’re nicknamed “history on a stick.” They’re intended to inform the public and mark the location of important historical events and people. According to Ansley Wegner, the administrator for the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, the state markers tell all sides of North Carolina’s history.

Wegner SOT: We don’t shy away from the difficult stories. We have a marker, just a couple of blocks from here about the Eugenics Board. We’ve got the marker about the Wilmington coup, we’ve got the marker about Greensboro massacre, we tell difficult stories. None of the markers are, are designed to praise people, they’re not honoring people, they’re just telling you that a person lived nearby or that this event happened.

Reporter: The first state historical marker was erected in 1936. Since then, the program has expanded and placed more than sixteen hundred markers across North Carolina’s 100 counties. Though, the language on some older markers is beginning to raise concerns.

Wegner SOT: we have a ton of markers that say slave on them, we can’t just go and replace them all you have a historical marker currently costs $1,860. … we don’t have the luxury or the funding to just take down markers and rewrite them, just because they have some old language on them.

Reporter: Despite the issue with older language, she says the goal is to get people’s attention and be brief.

Wegner SOT:They’re essentially a tweet. But we think that by having them large text People are going to read them, they’re a lot more likely to read them. … It’s not going to give them the whole story, but somebody might ride by and see Lunsford lane, formerly enslaved abolitionist, well, oh, I need to learn more about him.

Reporter: Deryn Pomeroy’s family loves historical markers.

Pomeroy SOT: When my father was a little boy, his father was a traveling salesman, so he’d be driving all over the place. And he’d often take my, my dad with them, and every time they would see a historic marker on the side of the road, they would pull over, and they’d get out of the car, and they’d read it together, which was a really sweet father son bonding opportunity.

Reporter: Pomeroy is the director of strategic initiatives for the William G. Pomeroy Foundation. It has partnered with the North Carolina Folklife Institute and the North Carolina African American Heritage commission to create markers for local Legends and Lore as well create the North Carolina Civil Rights Trail. Pomeroy hopes these new markers will have an impact on people.

Pomeroy SOT: “historic markers have, you know, a number of important benefits to communities, you know, they educate the public. We’ve seen at some of these dedications, we’ll have, you know, folks show up who had no idea that, you know, this, this event, or this happening occurred in their town. And it really encourages that that pride in place that perhaps wasn’t there before.”

Reporter: Both the State and the Pomeroy Foundation look to add more markers and tell more stories from history. In Raleigh, I’m Jackson Lanier.

End: 00:03:04

Pad: 00:03:04 – 00:03:15

Accompanying print story

By Laura Brummett

North Carolina’s Highway Historical Marker Program, represented by the 1,619 silver and black markers lining roads across the state, has been forced to pause its work acknowledging local and state history.

Money is short.

Run by the state Department of Transportation, the program has purchased no new markers since 2019 when the most recent one was erected in Raleigh commemorating Lunsford Lane, an enslaved man who bought his freedom and became an outspoken abolitionist.

Financial issues within DOT have cut the $60,000 program budget. Even so, the program is a one-woman show run by Ansley Herring Wegner. She oversees the applications, maintains old markers and writes the inscriptions for new markers.

Since 1936, when the first marker was erected in Granville County for John Penn, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the program has noted both the good and the bad in the state’s history.

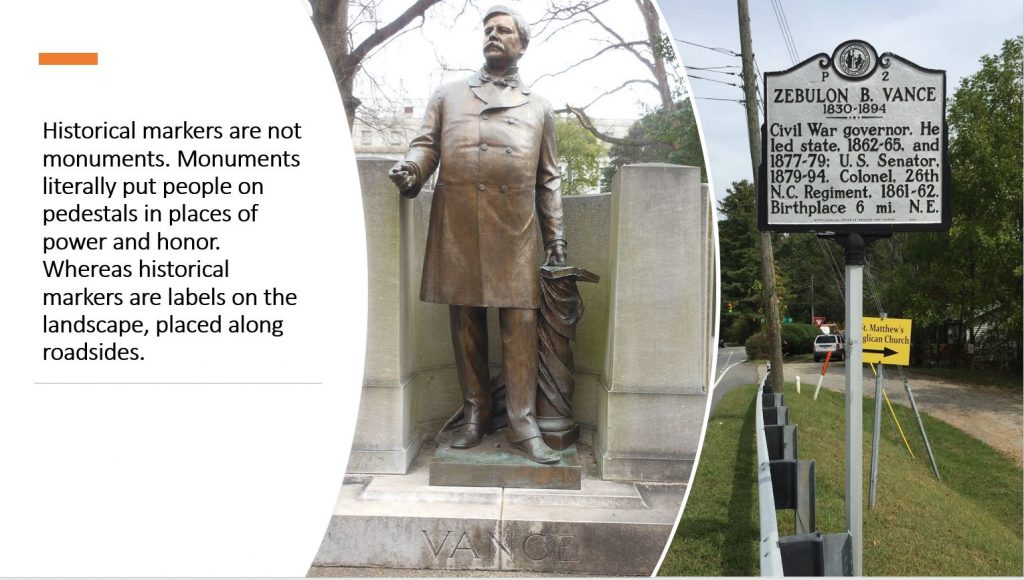

“We don’t shy away from the difficult stories,” she said. “We have a marker just a couple of blocks from here about the Eugenics Board. We’ve got the marker about the Wilmington coup, we’ve got the marker about the Greensboro massacre. None of the markers are designed to praise people. They’re not honoring people, they’re just telling you that a person lived nearby or that this event happened.”

When choosing inscriptions, Wegner is careful. Many existing markers dating back to the 1930s use wording that many people now find offensive. Some refer to Black people as “Negroes.”

If the budget returns, Wegner wants to replace the older offensive markers with new inscriptions.

Then there are the markers that get damaged or go missing. In one instance, a boat being pulled by a truck came unhooked and barreled into a marker, toppling it to the ground. The driver of the truck got out, hooked the boat back up and drove away.

The simple mishap was a blow to the underfunded program, because each marker costs $1,860.

During the summer of 2019, Wegner once saw a nine-day period where seven markers went missing.

Wegner is confident the program will be back, and she encourages citizens to continue submitting applications.

“I think more than anything, there’s just a lot of joy in seeing the markers that you’ve written,” she said. “And you can kind of remember how hard it was to come up with something that concise about a person or about an event and I just get a lot of joy out of knowing that people will pass them and it might spark their curiosity.”